I (Sasha) am once again grateful to Damian for lending me his readership to write about one of my favorite things: esoteric problems in local government.

Introduction

For the benefit of those living under rocks and/or outside of San Francisco: one of the city’s hot-button political issues is the layout of Valencia Street, a major corridor in the Mission neighborhood.

We’re going to take a brief look at how we got here, what the politics and feelings about the bike lane say about San Francisco more broadly, and where things might go from here.

If you’re reading this the day it was released, Valencia will be closed to cars tonight (Thursday, May 8th) from 5 to 10 PM for a bike lane ribbon cutting and the first in a series of Valencia Street Night Markets. Why are they cutting a ribbon? Read on!

What is Valencia Street?

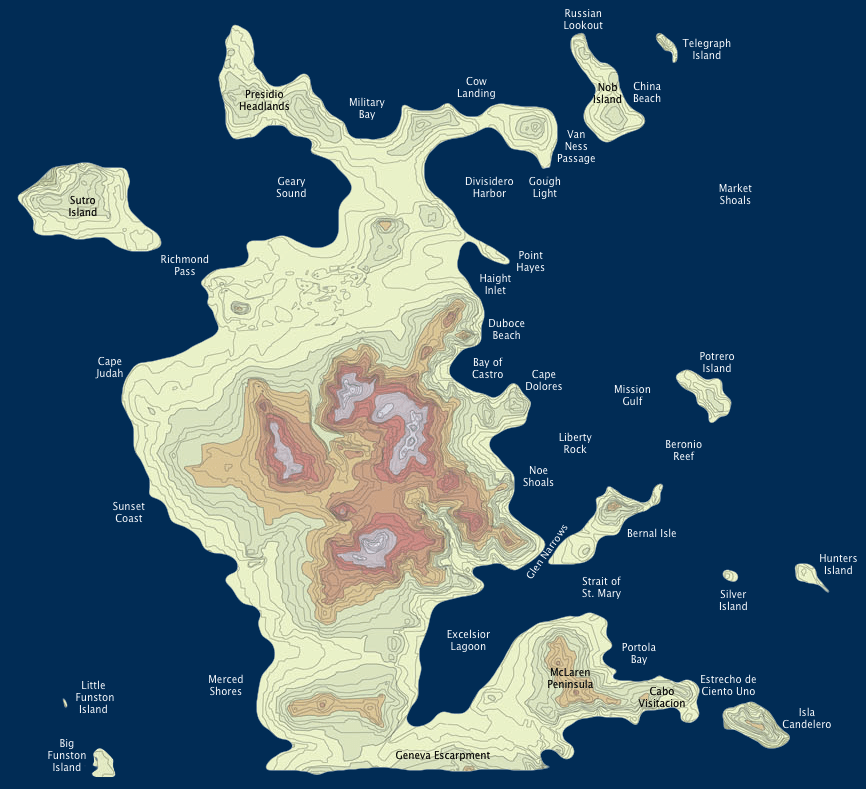

At one point, San Francisco looked like this:

Some time after, people arrived, followed a while later by people with guns and bibles, who established a mission, Misión San Francisco de Asís, eventually also known as Mission Dolores. One might say the were the first mission- driven organization in town, kickstarting the trend.

The city of Yerba Buena (renamed San Francisco in 1847) formed along the bay waterfront, while the Mission was basically an agricultural village located a few miles from downtown. The Mission had irregular dirt roads until the 1850’s, when it was incorporated into the San Francisco street grid to build housing for people coming to California for the Gold Rush. Valencia Street was built before 1863, when the corner of Valencia and 25th St was opened as the terminal of the San Francisco-San Jose railroad – the ancestor of what is today Caltrain. Valencia was originally built for streetcars (trams)1, connecting train passengers to destinations all over the city.

Almost every structure on Valencia was leveled in the 1906 earthquake, but the street was rebuilt, with streetcar tracks, wide sidewalks, and one travel and loading lane in each direction. The street stayed like this through 1949, when the streetcar tracks were paved over, sidewalks narrowed, and the street was reconfigured for two lanes of car traffic in each direction, plus parking.

Fifty years later, the subject of our story was born: the Valencia Street Bike Lane.

Two Decades of Doors

In 1997, Valencia was repainted, adding several feet to the outer lane in each direction. This made the lane wide enough to accommodate an informal, unprotected bike lane. Valencia is ideal for north-south biking in the Mission, as it’s unusually flat and cars are slower because of how many businesses are on it. Lobbying by the SF Bicycle Coalition and guerilla group bicycle rides by SF Critical Mass led the city to paint an official bike lane in 1999, though with nothing to keep cars out.

The bike lanes were popular, attracting thousands of daily cyclists by 2018. Commercial real estate on Valencia climbed in the 2010’s as bars, restaurants, and retailers competed for people’s zero interest-rate paychecks. Thriving businesses generate a lot of traffic: foot traffic from the bus and BART lines one street over, bicycle traffic, and car traffic – not only people driving themselves to shop but also delivery drivers dropping off people and goods and picking up food.

The mix of traffic was a recipe for injuries. Between 2012 and 2016, Valencia St averaged one vehicular collision per week – mostly cyclists being doored by drivers exiting their cars, followed by car-on-car collisions and drivers hitting pedestrians. The painted-on bike lane also became a de-facto loading lane for the 2010’s influx of food delivery drivers, forcing bike users into the danger of traffic.

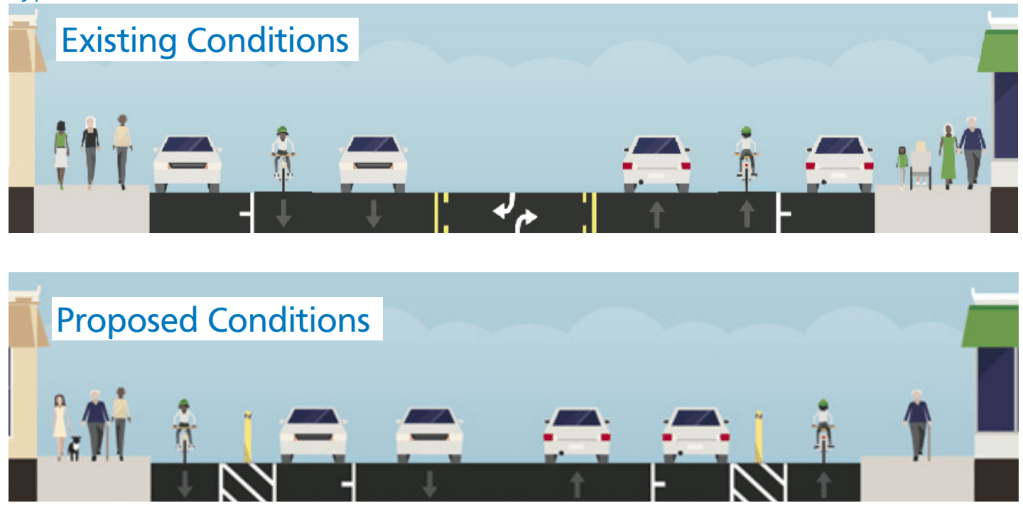

The SFMTA, responsible for transit, parking, and street safety in San Francisco, responded to this high rate of injury by piloting two protected bike lanes on the tips of Valencia. 500 feet of bike lane at the south of Valencia was changed to Dutch style, raised above the surface of the road, while 2000 feet at the north moved parking inward, serving as a barrier between drivers and bike users.

These pilots were fairly uncontroversial, and after years of outreach to residents and merchants, engineering drawings – showing the northern pilot design applied to eight of the unprotected blocks left on Valencia – were presented to the public. It was February of 2020. What could possibly go wrong?

Holy Shit Stuff Went Wrong

The Covid-19 pandemic happened. This, understandably, paused the Valencia bike lane improvements. It also threw a new curveball at the street design: parklets. To add outdoor seating in the time of respiratory disease, 2020 created sixty new parklets along Valencia.

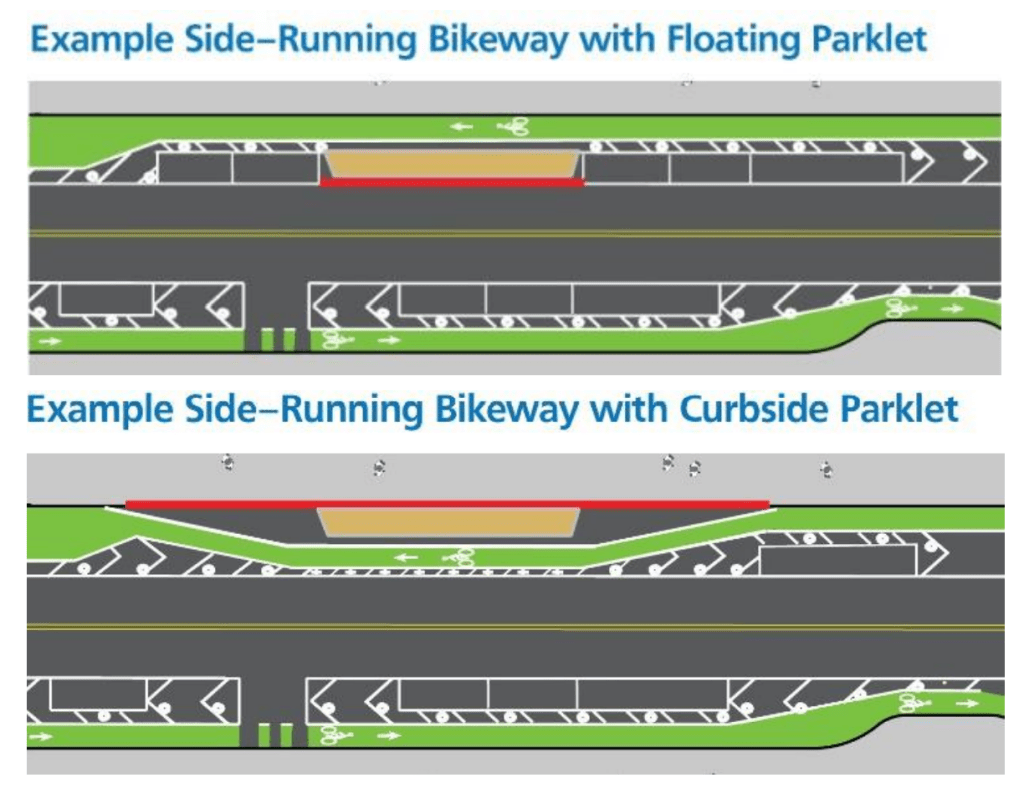

Treating a parklet like a parked car is challenging. The parklets generate a lot of foot traffic that wants to cross the bike lane, setting up conflicts between bike users and pedestrians. Parklets also need a level surface with the sidewalk to allow for wheelchair access, requiring bikes to go up and down a ramp at speed.

The alternative is to meander the bike lane around the parklet, which consumes curb space and removes parking spaces, with a trade-off between how many spaces are removed and how safe the transition is for bike riders. Going around the parklet also means neither a parklet nor a car separates bike users from traffic.2

Hoping to avoid these challenges, in 2022 the SFMTA decided to propose a novel design for Valencia Street.

Radical Centrism

The SFMTA proposed a new design which placed two directions of bicycle travel next to each other in the middle of the street, with a unique “funnel” intersection design to transition from the center to and from the edges of the street. This may sound strange or silly, and, well:

SFMTA polled local residents, and despite a 60% disapproval rating amongst those surveyed (including your humble author), the center-running lane was approved by the SFMTA Board of Directors3 and installed in the summer of 2023.

Meet the Losers

Several businesses closed after the center bike lane was installed. Among the most outspoken were Amado’s, a bar whose basement flooded, and Yasmin, a Middle Eastern restaurant whose basement suspiciously caught on fire. Despite those obvious problems, both claim the bike lane specifically forced them to close, and they’re joined by a chorus of other Business Losers who claim the center bike lane caused them to … lose business.

They place the blame on the removal of several dozen on-street parking spaces, which they claim made their businesses “impossible to get to”. This ignores the two large parking garages next to Valencia St and the many other ways of getting there – feet, several high-frequency Muni lines, BART, and *clears throat* the bike lane. When the SFMTA surveyed Valencia shoppers, 85% of them arrived by walking, biking, or transit.

Notably, almost all of the Losers are bars, restaurants and boutiques,4 which suffered from a confluence of post-pandemic changes: tech-focused layoffs cutting household spending, people moving in and out of the city, inflation raising prices, and the simple fact that running a restaurant is hard and most fail. Sales tax data support an alternate theory: Valencia Street is a competitive market, and when prices go up and customer budgets go down, the best businesses outcompete the okayest ones.

The Losers went on a relentless PR campaign, with antics like bodily blocking the bike lane and Yasmin’s owner going on a monthlong public hunger strike, and it was quite effective. A lot of local press ink was spilled on the new bike lane [1] [2] [3] [4], invariably calling it “controversial,” pulling quotes from a small group of merchants about how much they hated it, and uncritically repeating that the bike lane was responsible for their losses, in spite of the evidence. If you know anything about the “controversy,” it’s likely from this coverage.

Many business owners citywide use the same incorrect logic: “cars mean business 5, on-street parking means cars , therefore trading parking for safety means losing business .” The Losers fought so hard for airtime that businesses elsewhere in the city started using “Valencia Street” as shorthand for their opposition to street safety projects: “sure another driver killed a pedestrian here, but we can’t let the city do anything about it – look at Valencia!” This played out most notably in West Portal, after a quadruple homicide, where a driver killed an entire family – two parents and their infant children – as they waited for a bus to the Zoo. Imagine the response business owners would demand from the city if four people were killed in a gunfight on their street in broad daylight. Now read the West Portal Merchant Association’s response when the SFMTA proposed to prevent cars from entering the intersection where the driver killed the family:6

Seeking to capitalize on their favorable coverage, the Losers moved to try something new: suing for taxpayer money. The Losers filed formal complaints with the city, claiming that, by changing the (public) street in front of them, the city had infringed on their private property rights. The city refused their demands to change back to the painted-on side lane, after which the Losers threatened to sue. The theory of this case would be, without exaggeration, that businesses somehow own the public property outside their front doors and have a constitutional right to dictate what happens to it. This could lead to a court order to revert the bike lane and make the city pay damages, funded by tax revenue. As of this writing, the lawsuit remains theoretical.

Knowing bike lane history does not make me versed in constitutional law. What I can say is that this kind of attitude from local businesses is corrosive. San Francisco is full of small businesses, who’ve lobbied very hard to keep out large competitors, and this is supposed to be a good thing. It’s easy to find examples of national brands abusing their workers, stealing wages, price gouging, and lying to everyone. Small businesses are supposed to be better neighbors, because they’re directly accountable to the people around them. “I am entitled to public space and public money” is a big business level of contempt for your community. We have a constitutional right to tell people who say that to shut the fuck up.

Sorry, yes, we were talking about the bike lane.

Edge-Lords at the SFMTA

The center-running lane accomplished a key goal: convincing drivers they really shouldn’t stop in the area marked for bikes.

However, the SFMTA received a lot of negative feedback about the center-running lane. Some of it was genuine confusion from both bike users and drivers about how to use the street; a lot of it was incoherent hatred. There were also people who really liked the wide, center-running lane, which allowed them to bike slowly with children or more easily alongside a friend.

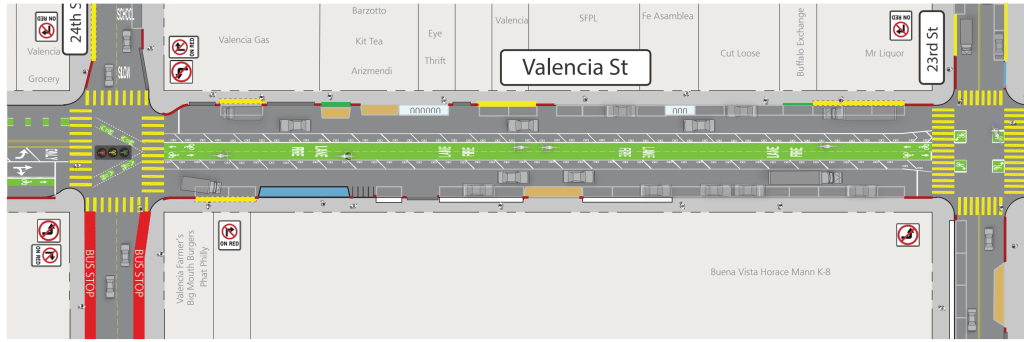

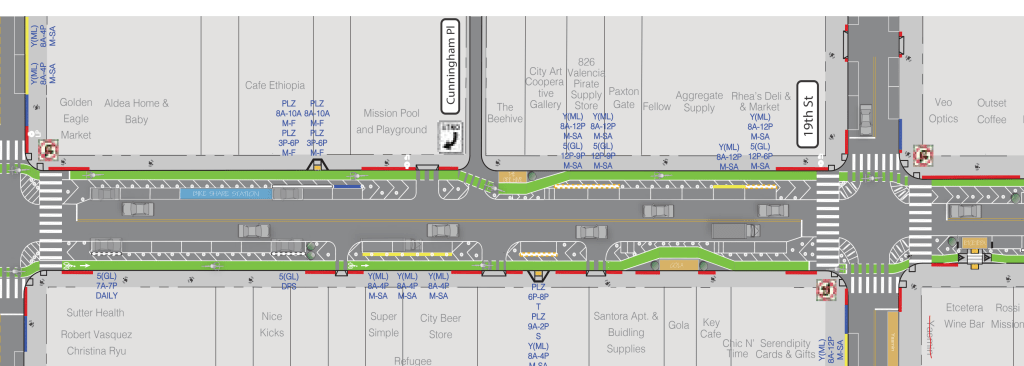

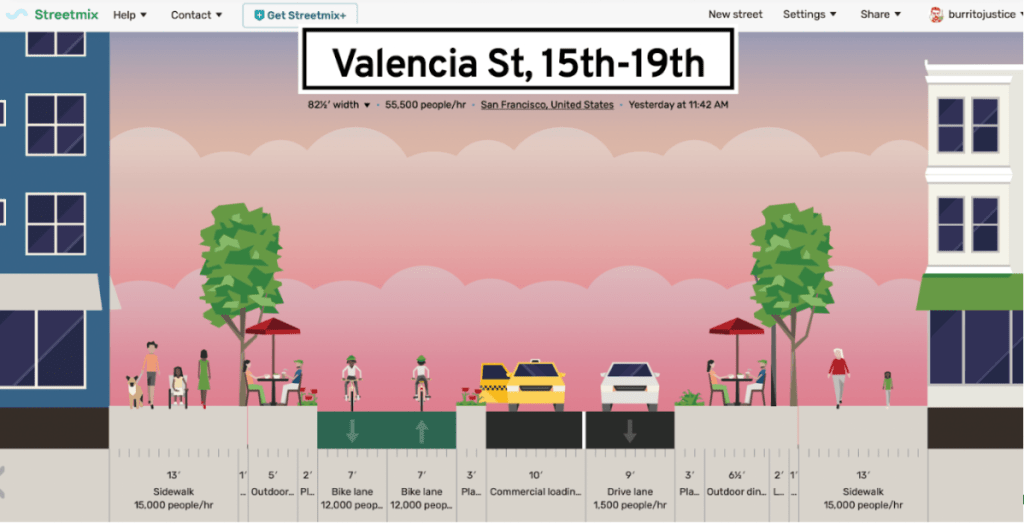

After the year-long pilot period concluded, the SFMTA decided to return to the Feburary 2020 plan – a bike lane, on the sides of the road, separated from traffic by parked cars.

This was more feasible in 2024 than in 2022 because roughly half as many parklets were left on the street. This made it easier for the bike lane to meander around them and reduced the number of parking spaces that would be removed. The new side-running design will have several dozen fewer on-street parking spaces than the pre-pandemic configuration,7 which can be easily absorbed by the two public garages within a block of the street.

The new design prompted a schism in the cartel merchant’s group representing Valencia businesses. The longstanding Valencia Corridor Merchants Association sent their leader, Manny Yekutiel (of Manny’s fame) to politely oppose the new design in front of the SFMTA Board of Directors.8 Our Losers formed a new astroturf organization9, “Vamanos,” and plotted a more aggressive Hail Mary to try and stop the new design.

This meant invoking CEQA, a California environmental law used by people who can afford lawyers to obstruct construction projects that annoy them. Vamanos couldn’t afford a very good lawyer, and the one they got filed a type of appeal that bicycle safety projects are explicitly exempt from.10 Vamanos presented a brief, incoherent case to the SF Board of Supervisors, supported by a few merchants complaining about the bike lane saga (and not the notional environmental concerns cited in the appeal). Twenty people – including Damian (see cover photo) and me – gave comment explaining how the appeal was plainly against the law, and the Board agreed, unanimously dismissing the appeal.

This procedural detour delayed construction on the new design by about three weeks, but it began in February, and as of this writing, final touches are being put on.

The Future (?)

The SFMTA maintains a “long term concepts” document for Valencia Street discussing bigger changes, like converting the street to one-way car traffic and placing a two-way bike lane on one side.

The so-called “Burrito Plan“

They also discussed pedestrianizing the street, permanently closing it to through-traffic while leaving it open to pedestrians, bicycles, and some local and delivery traffic. This is common in global cities that San Francisco likes to compare itself to, like Copenhagen, Bangkok, or even the Spanish city of… Valencia. Bay Area neighbors like Mountain View, San Mateo, and (legendarily regressive) Palo Alto have also pedestrianized key commercial streets with widespread success. Valencia was regularly closed to cars for three days a week during the pandemic, and has been intermittently closed for festivals since then.

There are some practical challenges with both of these long-term visions11, and I think the experience with the center-running lane rattled a lot of staff at the SFTMA and the elected officials who oversee them. I’m not holding my breath for more serious change – I think it would require a key politician – either the District 9 Supervisor12 or the Mayor themselves – willing to navigate the politics of taking the next step.13

That means the side-running lane – a long-awaited, modest improvement on the design first built in 1999 – is probably here to stay indefinitely. Better things are absolutely possible and worth fighting for; yet at the same time, we now have the safest and most normal bike lane that’s ever been on this street. This too will likely see some “controversy,” but remember that this is, for the most part, a handful of angry business owners thrashing against the idea of competition and lusting after a city bailout.

Making it safer to bike around our city means more people will do it. Even if you’ve never touched a bicycle, you benefit from others doing so – traffic gets lighter, parking is more abundant, and the world warms a little less. Those benefits require a little bit of compromise, but not much more than walking a few minutes from a parking garage. That little walk is another benefit, for small businesses, called foot traffic. I hear some places on Valencia would really like more of it.

While I Have Your Attention…

If you thought this was interesting, you may also enjoy:

- Trip Report: Damian’s ride on the Shimanami Kaido Bike Route

(coming soon!) - This fantastic video essay from a friend of mine14, where she talks about many of the other street safety challenges in San Francisco

- How California state lawmakers are, quietly, deciding whether or not it will be possible for the US to elect a Democratic president after 2032 (default option is “no”)

Footnotes

If you actually clicked on one of these, thank you. I saved the juiciest nuggets just for you ❤️

- Prop L author and Renaissance enby Chris Arvin has a very helpful map of former SF streetcar routes. They’re the direct ancestors most of the lettered light-rail routes in SF today (the J, K, L, M, and N, which all ran their current routes under those letters in the 1920’s). Most of the streetcars had their tracks paved over became Muni busses (some with the same numbers and routes as today, like the 14 and 22). Of note to our story is the 9 Valencia streetcar, which ran the whole length of Valencia and onto Market Street. The Valencia streetcar eventually became the 26 Valencia Muni bus route, which ceased service in 2009. Starting July 1st, 2025, Muni will once again have a Route 26, formed out of the merger of the 21 Hayes and 6 Haight-Parnassus bus routes (this is bad, but that’s another story). The 26 Valencia is memorialized in a mural in the back patio of Valencia Street burrito institution Señor Sisig. ↩︎

- The SFMTA could, in theory, install thinner concrete or steel barriers to separate the car lanes from the bike lanes and parklets, but not in practice due to the fire code. The standard US Fire Code – pretentiously called the International Fire Code, despite being written by Americans and used almost exclusively by Americans – sets rules for the design of streets to ensure that fire trucks can traverse a city quickly, and they effectively ban safety barriers from most city streets. It’s worth noting that barriers, steel bollards, and fire trucks coexist peacefully everywhere else in the world and that American fire departments are uniquely concerned with making it easy to drive around dense cities at speed. For more on the strange, outsized negative role that fire departments have on local politics, this is a great read. ↩︎

- I was actually in the hearing room watching the board discussion; many community members gave public comment both for and against the lane. I did not personally comment during the designated part of the hearing, but the San Andreas Fault did, sending a magnitude 4.6 earthquake in what can only be interpreted as a sign of disapproval. ↩︎

- There are a handful of auto shops on Valencia opposed to the bike lane for obvious reasons; I’m ignoring them in the main narrative because they’ve been a lot less outspoken and because their circumstances are unrepresentative of most of the businesses on Valencia. ↩︎

- Every survey the SFMTA has run shows the same thing: the overwhelming majority of people shopping on commercial corridors in San Francisco got there by walking, biking, or taking transit [1][2][3][4]. Merchants and merchant-aligned city officials applying the toddler logic of “‘I see cars driving by’ means ‘businesses here are thriving’” is likely also responsible for recent lobbying to let cars onto Market Street, which is a bad idea for many reasons. ↩︎

- The proposed changes at this intersection would not only make it safer but also significantly improve the efficiency of Muni trains passing through. The intersection in question is the “west portal” of the Muni tunnel under Twin Peaks, with gave the neighborhood its name and brought it into existence. ↩︎

- Two caveats: first, new statewide “daylighting” laws – mandating the removal of parking spots near crosswalks to make pedestrians more visible to drivers and thus making it safer to cross the street – are responsible for 20% of the total reduction in parking spaces. The bike lane uses space that would otherwise need to be left empty, and thus the bike lane didn’t “take” those spaces. Second, in both bike lane updates, the SFMTA allocated a lot more curb space to loading, given how many drivers used to stop in the bike lane to pick up orders or drop off passengers. This means the number of parking spaces previously on Valencia was artificially high, as space allocated to parking should have been marked for loading instead, rather than relying on illegal short-term parking in the bike lane. This makes the parking reduction of the new design even more modest. ↩︎

- This was extremely funny to watch because Manny was a member of the SFMTA Board of Directors when the center bike lane was proposed, and he gave an Aaron Sorkin-style speech (see here, 3:17:30) on the centered design and on the virtues of local government innovation prior to casting his “yes” vote. Two years later, Manny had resigned his seat on the Board (for unrelated reasons) and changed his tune, railing against both the center-running lane and the proposed improved side lane, and pleading with the SFMTA to throw it all out and go back to the design that he, as an appointed city official, called dangerous and an attempt “to do too much with too little space.” ↩︎

- “Astroturf” being in opposition to “grassroots,” describing an organization that tries to seem larger and more genuine than they actually are. Vamanos doesn’t publish their membership but has previously indicated a single digit number of member businesses. Their representatives at their appeal pronounced their name “va-MAH-nos,” indicating they speak less Spanish than Dora the Explorer. Their logo is literally a drawing of Valencia Street devoid of cars (which, on close inspection, also appears to have been AI generated). These are unserious people. ↩︎

- The specific legal filing was a “CEQA determination appeal,” which allows the elected members of the Board of Supervisors to review the environmental law compliance of any action taken by the unelected departments of the city. Vamanos was legally entitled to a hearing to have the Supervisors confirm that compliance, and it’s pretty clear their plan was to try and politically lobby the city’s elected officials to claim the project didn’t comply, in violation of the plain text of the law. Bicycle projects are inherently compliant with state environmental law thanks to a bill written by San Francisco’s state senator (Scott Weiner) several years ago. This law was inspired by a protracted CEQA battlebetween the city and a different group (the “Coalition for Adequate Review”) that sought to stop the city from implementing any bicycle infrastructure. This lawsuit successfully halted all city bicycle work between 2006 and 2010, and lives on in infamy under the incredibly topical name “CAR v. City and County of San Francisco.” ↩︎

- The SFMTA claims that converting Valencia to a one-way street would require a ~$30M traffic signal modernization project, based on the very limiting assumption that you could not convert the street without replacing every single traffic light (traffic lights are, in fact, that expensive). Pedestrianizing the street is a lot more complicated as Valencia has a police station and businesses that need to get deliveries. There is also a genuine traffic problem routing trucks north and south through the neighborhood – Valencia is sandwiched between Guerrero and Dolores Streets, which are too hilly to drive a box truck on, and Mission Street, which has the second most bus traffic of any street in the city and accordingly has very complicated traffic rules. These are surmountable problems, but the SFMTA is not lying when they say they’re hard. They’d be more surmountable and faster to solve if SFMTA staff didn’t feel politically pressured to listen to literally hundreds of hours of whining, as they did during the Valencia project. ↩︎

- Newly elected supervisor Jackie Fielder said, in a pre-election interview about the bike lane, that she thought there was not enough discussion about it and that she would have facilitated more, which is, uh, a position. “More discussion” has been the playbook used elsewhere in the city to kill off street safety proposals; in West Portal, the “Welcoming West Portal Committee” was convened to welcome the Spectre of Death back to West Portal Avenue. Credit where it’s due to Supervisor Fielder: as a candidate, she attended the last public SFMTA event discussing the move back to a side-running bike lane and seemed genuinely pretty interested in just listening to what people had to say about it. As the local Supervisor, she led the conversation when Vamanos’ appeal landed in front of the Board, and she made it clear from the start that she agreed the appeal was plainly against the law and that no further discussion was needed. ↩︎

- There are two ways this might get better over time. Sustainable “urbanist” ideas have made slow but steady gains in San Francisco, and “hey we want to make it easier for you to walk around and do fun things” is one of the easier sells. There is also quiet background chatter around establishing a “street capital projects impact fund” to pay out to businesses disrupted by street infrastructure projects (transit construction, bike lane construction, new traffic patterns to facilitate pedestrianization, etc). This policy idea is a Machiavellian acknowledgement that if you’re dealing with rent-seekers, both you and they will get a positive outcome faster if you bribe them rather than try to fight them. ↩︎

- I met her through volunteering for the 2024 Prop L campaign! If you want cool friends, go get involved with a campaign where you live in 2026 (or this year, if you live somewhere freaky). Whether you’re in SF, Cambridge, Dodge City, or one of America’s other, lesser cities, there will almost certainly be a question of “right” or “wrong” on your ballot, and if 2024 taught us anything, a lot of Americans need a flesh-and-blood person, in their face, politely telling them which is which 🙂 ↩︎